OSA continues to join farmer, consumer, and rural advocacy organizations in urging the US Department of Justice (DOJ) to block the proposed merger between Bayer and Monsanto.

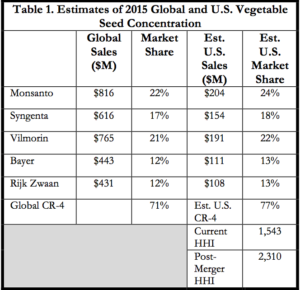

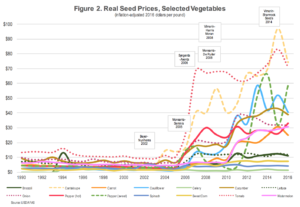

In a letter sent today to DOJ two dozen groups detailed the potential anticompetitive effects of the proposed $66 billion merger on the vegetable seed market. The proposed deal would join the world’s largest and fourth largest vegetable seed companies and would further consolidate the already highly concentrated vegetable seed industry (see Table 1). If this merger goes through, farmers will likely pay more for a diminished array of seed options. Vegetable seed prices have increased tremendously alongside mega-mergers in the vegetable seed industry (see Figure 2).

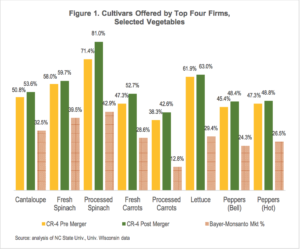

Today, the largest vegetable seed companies are vertically integrated firms that research and breed varieties, multiply and manufacture seeds, and distribute and market seeds to farmers. Only a few vegetable seed companies dominate the market for each commercial vegetable crop (see Figure 1), and these companies are primarily interested in a relatively narrow set of high-value vegetables.

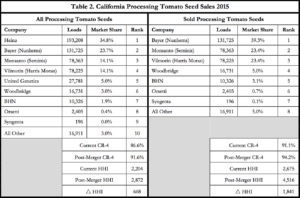

The proposed merger joins major rivals that compete to sell many vegetable varieties, including tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, lettuce, carrots, spinach, and onions in the $860 million US vegetable seed market. The letter conservatively estimates the two firms would control more than 37% of the US vegetable seed market, but likely would sell more than half — and likely much higher for some vegetable varieties. For example, a combined Bayer-Monsanto would sell an estimated 62% of California processing tomato seeds (see Table 2).

Monsanto’s aggressive merger strategy has allowed it to maintain dominance in the seed industry. From 1995 to 2015, the company purchased 19 seed companies — about two-thirds of the company’s takeovers. In vegetables, beginning in 2005, Monsanto bought Seminis for over $1 billion, a deal that gave Monsanto control of 39% of the US vegetable seed market and 26% of the global market. In 2008, it added the $800 million purchase of De Ruiter Seeds, which specialized in greenhouse vegetable seeds.

Monsanto’s aggressive merger strategy has allowed it to maintain dominance in the seed industry. From 1995 to 2015, the company purchased 19 seed companies — about two-thirds of the company’s takeovers. In vegetables, beginning in 2005, Monsanto bought Seminis for over $1 billion, a deal that gave Monsanto control of 39% of the US vegetable seed market and 26% of the global market. In 2008, it added the $800 million purchase of De Ruiter Seeds, which specialized in greenhouse vegetable seeds.

The Bayer – Monsanto merger will likely reduce the choice of varieties that farmers can plant, as companies like Monsanto have shut down brands and reduced their lines after completing mergers. The letter estimates that the two companies currently control a substantial portion of varieties for many vegetables — 43% of processed spinach, 33% of cantaloupe, 30% of lettuce, and 29% of fresh carrot varieties, to name a few.

The Bayer – Monsanto merger will likely reduce the choice of varieties that farmers can plant, as companies like Monsanto have shut down brands and reduced their lines after completing mergers. The letter estimates that the two companies currently control a substantial portion of varieties for many vegetables — 43% of processed spinach, 33% of cantaloupe, 30% of lettuce, and 29% of fresh carrot varieties, to name a few.

History shows us that mergers of this scale typically reduce rather than inspire innovation. The majority of commercial vegetable seed companies have proprietary control over their seed lines through hybridized techniques and/or through the enforcement of restrictive utility patents or licensing agreements on seed varieties and genetic traits. These intellectual property rights are typically aggressively enforced, disallowing farmers to save seed and often prohibiting research on the protected genetic material.

What does this mean for organic farmers? Though neither Bayer nor Monsanto are players in the organic seed trade, many organic farmers rely on their untreated (sans chemical pesticides) varieties. And because organic farmers are already underserved by the dominant seed trade, this merger could exacerbate this problem by further concentrating and privatizing vegetable genetics, reducing choice in the marketplace and making it more difficult for other seed companies to compete. At the end of the day, giving more market power to companies that only invest in seed technologies and chemical farming systems that are in conflict with organic practices isn’t only a bad deal for organic farmers, it’s a bad deal for all farmers, farm workers, and consumers who desire a healthier food supply, work environment, and planet.