Contents

The following guide was written by Paulina Jenney and adapted from her professional paper, “Keeping What You Sow: Intellectual Property Rights for Plant Breeders and Seed Growers,” submitted in May 2022 to the University of Montana.

Introduction

Over the last 150 years, much of the world’s plant genetic diversity in our food system has been lost, due primarily to the industrialization of agriculture and consolidation of power within the seed industry.1

Emboldened by federal laws and legal decisions during the 20th century, major companies and other plant variety developers have tied up seeds and genetic traits with restrictive intellectual property claims, an arrogation of policy that had been conceived to spur innovation in plant breeding and increase the diversity of seeds available to farmers. Instead, these political and economic forces have created a market structure in which just four companies control 60% of the world’s seed stock.2

These companies have systematically prioritized crop traits that improve production—traits like uniformity, yield, and agrochemical resistance—at the expense of traits that strengthen plant varieties against environmental pressures—traits like diversity, regional adaptation, and low-resource use.

As the climate destabilizes, the predictable seasons, soil health, and water availability that once supported monoculture and industrial farming will continue to become more chaotic. A movement of independent seed companies, breeders, growers, and stewards are focused on maintaining and increasing seed biodiversity to create varieties that can thrive in the coming world. These projects require financial resources to maintain access to land, equipment, and labor. To recoup those costs, many people who seek to market seed, especially of new or novel varieties, are left to try to reclaim strategies in intellectual property rights (IPR)—the same legal mechanisms that have historically served to narrow the genetic diversity of our crops.

Because the application of intellectual property rights to living organisms is a relatively recent and ill-defined concept, both biologically and in its lack of legal precedent, there remains considerable uncertainty about how diversity-focused seed growers should approach the question of protecting the integrity of their seeds and their livelihoods in a changing legal and economic landscape. Much of the uncertainty around alternative intellectual property rights strategies for seed growers is because adapting traditional intellectual property systems, which are intended for immutable inventions, to living organisms has not been an easy task. As a result, Congress has experimented with a number of legal systems over the past century, resulting “in a confusing array of overlapping intellectual property regimes” that are difficult to navigate and unevenly applied.3

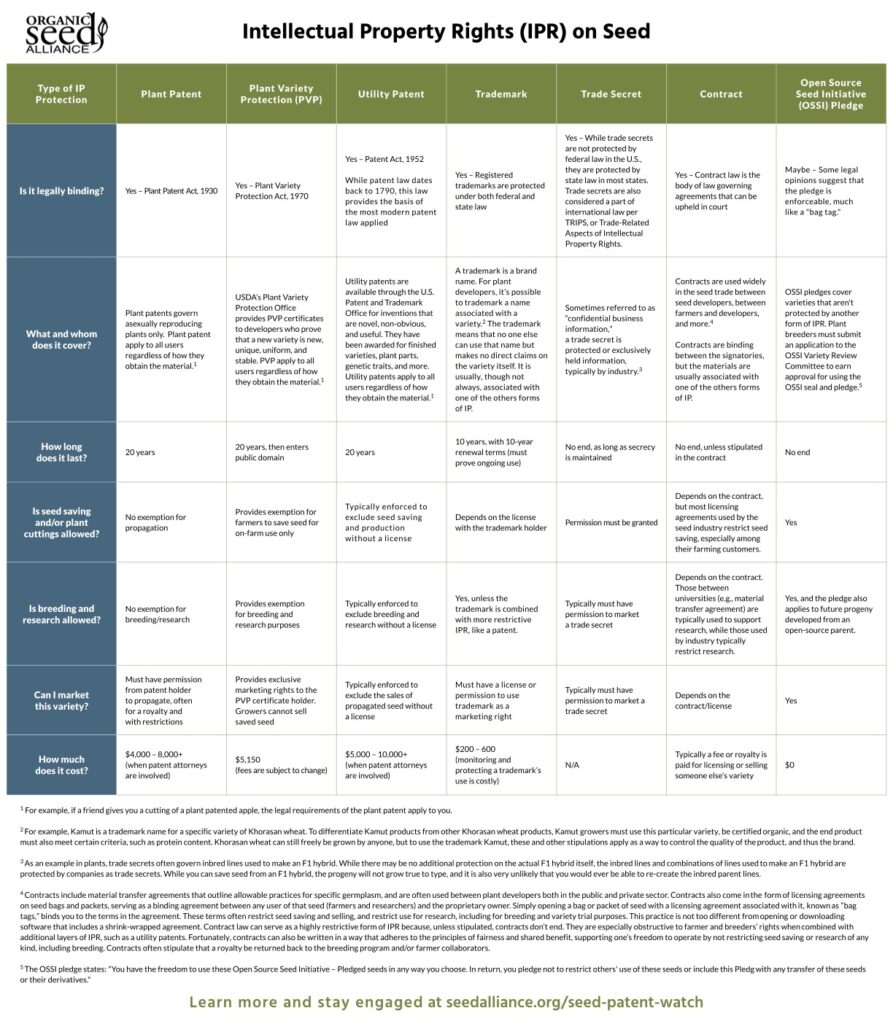

Even the term “IPR” is commonly used to refer not only to avenues for protection offered through the United States Patent and Trademark Office, but also for strategies that route through the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service, in addition to contract law and defensive systems designed by non-profit advocacy and community groups such as the Open Source Seed Initiative, seed banks, and exchange networks. Often the onus of deciphering the different intellectual property strategies and navigating the application process rests on the originators of the seed, many of whom have little experience or financial resources to confront the legal arena.

A goal of OSA’s program work is to confront the concentrated ownership of seed as a living, natural resource, which includes addressing consolidation of market, economic, and political power in the seed industry. We believe restrictive intellectual property rights on seed, such as utility patents, run counter to the spirit of patent law and stifle innovation, creating barriers to improving the availability and integrity of organic seed, as well as growers’ ability to adapt crops to changing climates and to conserve culturally important varieties.

Data Collection and Methods

In January 2020, OSA held a virtual listening session on “Seed Commons & Ownership,” during which seed growers from a range of backgrounds shared their questions and concerns. The session had over 150 people in attendance, a testament to the currency and importance of the topic across a wide cross-section of people who work with seed. Attendees represented a multitude of affiliations, from university plant breeders to home gardeners, independent plant breeders seeking to protect their varieties using IPR, to small farmers worried about inadvertently growing IPR restricted seeds. In this way, seed workers from seemingly opposite sides of the conversation were united by a common desire to improve the resilience of the food system. Participants frequently noted that the IPR conversations among farmers, breeders, farmer-breeders, and seed savers are “complex” and “nuanced.” In a post-session survey, one participant noted that they would like to see “specific examples (names of varieties, people, timeline, etc.)” that could illustrate the different strategies organic plant breeders and seed growers leverage to navigate the modern world of intellectual property rights. This reflects a need that has long been vocalized by the growers served by OSA, who have for years expressed confusion about the overlapping, seemingly contradictory array of intellectual property strategies and their actual impacts on breeding and seed saving work.

In 2021, OSA also integrated a module on seed sovereignty and intellectual property rights into their “Organic Seed Production” course, an annual, online curriculum offered to beginning seed growers for free thanks to a grant from the USDA Beginning Farmer and Rancher Development Program. Students in the course were asked to go through an application process that demonstrated a commitment to seed production as a serious practice or a livelihood. The course ran for six months and included modules on crop selection, variety maintenance, harvesting, and cleaning. The participants in the course and, by extension, the module on intellectual property rights, were more narrowly selected than those who participated in the January 2021 listening session, which was open to the public. During the module, participants were asked to populate a list of questions they had about IPR. A sampling of those questions includes:

How long has IPR been a thing? Who manages or oversees IPR? Does IPR apply to heirloom seeds? What are the consequences for violating IPR? How well is this working internationally? How does IPR function with Indigenous seeds and within tribal communities? How can we reward the time and energy of seed breeding without resorting to capitalism, ownership, and property?

The fact that there are significant and persistent questions about the role of IPR as they apply to seeds, even among seed producers, highlights the need for a resource that increases literacy around the topic in a format that is easy to read, understand, and put into practice.

Between February 2021 and February 2022, we interviewed 21 seed growers representing a variety of backgrounds in seed production, from backyard gardeners to keepers of local varieties, to university plant breeders, to owners of seed companies both small and large. Some interviewees had engaged with some form of intellectual property protection, and some had not. During each interview, we asked each participant what type of crop they grew, their perspective on intellectual property and seed marketing in general, and to voice any questions they still had about IPR, among other questions more specific to each individual. We were able to talk to less than half of those contacted for an interview, with the majority of people who declined to participate citing a lack of time as their reason for not agreeing to an interview. The sample size means that participants in this study represent a very limited cross-section of the vast and diverse community of people involved in organic seed work; still, this constitutes a good starting point for beginning to understand some common themes and approaches to IPR that people who work with seeds tend to have.

In this guide, you will find insights from those interviews, including special “Seed Stories,” in which a particular grower shares their experience and strategy for navigating intellectual property rights. You will also find answers to some of the more common questions that emerged from participants over the course of this research. Still, many questions remain about how to ethically market seeds in the modern agricultural landscape. In this way, while the guide attempts to answer some questions, it also raises many others. Many of the questions approached here do not have easy, clear-cut answers, and instead seek to provide a “toolkit” that consolidates as much of the current information available as possible into a single, searchable resource for the organic plant breeder or seed grower.

A note: this guide specifically addresses how IPR laws in the United States affect small-scale and agroecologically aligned seed growers working within the United States. While international and tribal laws pertaining to IPR play a significant role in the way that seed is traded across borders, and have potential to shape federal policy, investigating multiple legal frameworks is beyond the scope of this project. One particular opportunity for research that emerged during the latter parts of this project is to explore the way that tribal sovereignty might be leveraged to protect Indigenous seeds from encroachment by federally recognized IPR.

How this Guide is Organized

Chapter One provides a brief overview of the ascendance of intellectual property rights in the seed industry in the United States, and unpacks the problem at hand by describing the legal and economic decisions that led to its creation. This chapter also introduces the relationship between colonialism and intellectual property rights and the role of the USDA National Plant Germplasm System in conservation and breeding efforts. Noah Schlager discusses Indigenous seed keeping and how non-Indigenous people can engage with culturally important seeds.

Chapter Two explains the nature of utility patents and makes the argument that they are the wrong strategy to protect seeds and encourage innovation in agriculture for ethical and practical reasons. This chapter also explains the patent review process and the legal implications for growing patented seed. This chapter explores why, despite the incongruities, some companies still patent their seeds. In “Seed Stories,” Edmund Frost describes the impact utility patents can have on public breeding projects. This chapter also provides the reader with resources for searching and understanding the utility patent database.

Chapter Three answers questions about how to publish the existence of a variety in a way that can preempt restrictive intellectual property claims before they arise. This chapter explains the components of a defensive publication and how to leverage those publications to challenge a pre- or post-grant patent application.

Chapter Four defines intellectual property mechanisms which can still be utilized in ways that do not restrict seed saving or plant breeding, including Plant Variety Protection certificates, trademarks, and trade secrets. This chapter explains the time and resources implicated in each of these strategies. In “Seed Stories,” we hear from Jim Myers, a public plant breeder from Oregon State University, and Jason Cavatorta and John Hart, private breeders for EarthWork Seeds. Both stories depict the use of PVPs to recoup investment costs on novel varieties that are the result of focused breeding projects. Dave Oien of Timeless Seeds and Tessa Peters of The Land Institute share their experience trademarking varieties. In these stories, both Oien and Peters describe the potential benefits of trademarks that other IPR strategies might not offer.

Chapter Five breaks down the most popular iterations of contract law in plant breeding, which is often paired with the other, more formal strategies for intellectual property protection. This chapter covers Material Transfer Agreements (MTAs) as a mechanism for exchanging seeds for research, both by universities and seed banks, as well as how MTAs are leveraged in international seed collection and germplasm exchange, especially in collections involving Indigenous seeds. This chapter then describes the various forms of licensing contracts and royalty agreements used in the seed industry. Although the OSSI pledge is not so much a formal contract as it is a social one, this chapter also includes a description of the OSSI pledge, and a “Seed Story” from Craig LeHoullier and his reasons for using the OSSI pledge with the tomato varieties that emerge from the Dwarf Tomato Project.

Chapter Six provides an analysis of all of the interviews conducted for this resource, and uses their contents to support the themes that emerged from a previous OSA Intensive meeting on Seed Ethics. This chapter explores the various ways that plant breeders and seed growers from different backgrounds approach 1) transparency along the seed value chain, 2) ethical recognition of breeders’ and seed savers’ past efforts, 3) ethical compensation for breeders and seed growers maintaining the seed system, and 4) the importance of biodiversity as a goal for all people who work with and transact seeds.

Abbreviations

| ABS | Access and benefit-sharing |

| AppFT | Application Full-Text and Image Database |

| AIA | America Invents Act |

| ASTA | American Seed Trade Association |

| BASF | Badische Anilin – und Sodafabrik (German agrochemical company) |

| CBD | Convention on Biological Diversity |

| CIAT | International Center for Tropical Agriculture |

| CPC | Cooperative Patent Classification |

| GE | Genetically engineered |

| GMO | Genetically Modified Organism |

| GRIN | Germplasm Resources Information Network |

| IPR | Intellectual Property Right |

| ITPGRFA | International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture |

| JPR | Journal of Plant Registrations |

| LGU | Land Grant University |

| MTA | Material Transfer Agreement |

| NPGS | National Plant Germplasm System |

| NSS | Native Seed/Search |

| OSSI | Open Source Seed Initiative |

| PatFT | Patent Full-Text and Image Database |

| PE | Patent Examiner |

| PPA | Plant Patent Act |

| PVP(A) | Plant Variety Protection (Act) |

| SARE | Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education |

| TKDL | Traditional Knowledge Digital Library |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| USDA-ARS | USDA – Agricultural Research Service |

| USPTO | US Patent and Trademark Office |

CHAPTER 1: How Did We Get Here?

The Ascendance of Intellectual Property Rights Over Seed

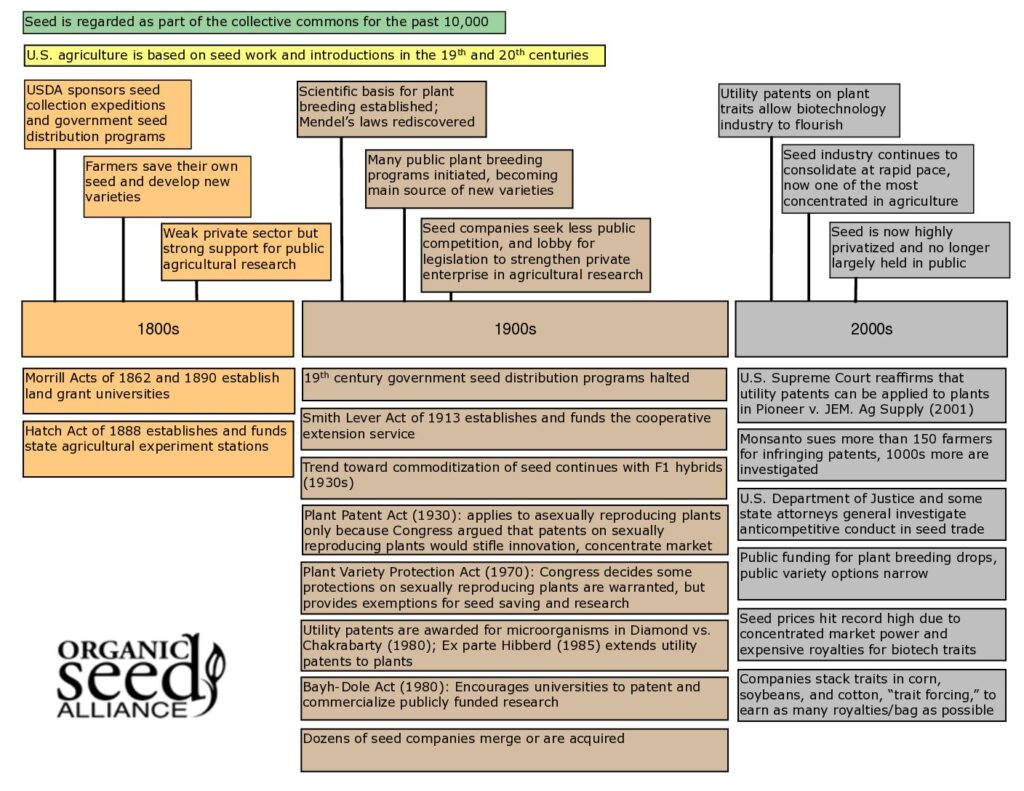

People have been breeding plants for over 10,000 years; yet, the application of intellectual property law to our seed system has only really been in effect for less than a century. During this century, advancements in plant breeding have evolved considerably, and federal policies have tried but failed to keep pace (see Figure 1: Seed and IPR History).4 This chapter explores the rise of intellectual property rights on seed in the United States and their effect on consolidation of power in the seed industry.

In August 1931, the United States Patent Office (USPTO) issued its first ever plant patent to a man named Henry Bosenberg for a “new and useful improvement” of a Van Fleet rose under the newly signed Plant Patent Act, which created intellectual property rights for the improvement of plant species. A number of inventors and plant breeders (Thomas Edison among them) supported the Plant Patent Act, arguing that such legislation would spur agricultural innovation.5 Ironically, Bosenberg was neither a plant breeder, nor had he invented anything new. Bosenberg had simply noticed an ever-blooming rose growing in his garden, a naturally-occurring anomaly borne of the Van Fleet variety, and increased its population through propagation. Still, through the Plant Patent Act, the USPTO ruled that Bosenberg could lay claim to the existence of this “new variety.” Almost immediately, the managing editor of the Journal of Heredity took issue with the patent, pointing out a number of “interesting problems,” the primary one being that Bosenberg had averred under oath “that he did nothing to originate the new form.”6 Still, it is likely that the USPTO viewed the application as valid because the plant was a unique anomaly among a relatively stable population, and it had the ability to be propagated and marketed. After all, the primary impetus behind the Plant Patent Act was to respond to complaints from the nursery industry, who encouraged lawmakers to curtail the “pirating” of novel varieties, whether they were “invented” or merely discovered.7

Prior to the passage of the Plant Patent Act, the USPTO was in charge of collecting and disseminating free seed to farmers, and farmers would then go on to develop improved crop varieties, adapting the seeds to their particular region through careful observation and selection.8 While this was useful for farmers growing produce, there was no compensation for the farmers breeding and producing new seeds. Conservative lawmakers and pro-industry leaders (united under the American Seed Trade Association) considered the USPTO’s seed program antithetical to interests of the nascent seed industry and campaigned for plant breeding to transition from a publicly supported science to private industry.9,10,11 Thus, the spirit of open and free seed trade, which had proliferated for thousands of years, was effectively curtailed for the first time in the name of industry.

Initially, the Plant Patent Act was only designed to cover plants that reproduce asexually (like roses, some berries, and some stone fruit trees, which can be cloned), and excluded sexually produced (pollinated) plants like corn and soybeans. Because those plants relied on pollination, the Patent Office did not think that their seeds could produce genetically stable varieties.12 The American Seed Trade Association disagreed and eventually lobbied for the creation of the Plant Variety Protection Act in 1970. The PVPA grants exclusive marketing rights to the developer of a new variety of sexually reproducing plants for 20 years as long as the new variety is “new, distinct, uniform, and stable.”13 The ASTA recognized that farmers could reliably reproduce non-hybrid seeds from one generation to the next and had no need to return to the seed company after buying from them once. Further, seed growers were able to market future generations of seeds without any of the research and development cost borne by the original breeder or seed company.14 Still, the PVPA made specific exemptions that allowed farmers to save seed from protected varieties for on-farm use. Further, under a PVP, breeders can purchase seeds from other companies for use in their own breeding programs as long as the result of their efforts is a new variety with at least one distinct morphological trait.

In 1980, the Supreme Court heard Diamond v. Chakrabarty, a case concerning genetically engineered microorganisms. The court ruled that anything “man-made under the sun” was eligible for a patent, including living organisms. However, Congress had already acknowledged, through the passage of the PVPA, that intellectual property for plant breeders necessitated specific exemptions to preserve the nature of plant breeding, which for millennia has relied upon seed saving and the exchange of seeds for breeding and research. Breeders claimed that these exemptions left their inbred and self-pollinated lines vulnerable to piracy and forced the USPTO to address their concerns in ex parte Hibberd, which held that a corn breeder could apply for a utility patent on a variety of corn that had increased free tryptophan levels. Hibberd further ruled that even breeders of self-pollinating and inbred crops could apply for utility patent protection.15 This meant that plant breeders could prevent other breeding programs from using their seeds for research, a ruling that circumvented the farmer’s exemption available in a PVPA. In addition, while plant patents and PVPs only apply to entirely new varieties, and expire after a certain amount of time, a utility patent can be granted for a certain color inherent to a plant, or a particular disease-resistant trait. Moreover, a company can renew a utility patent after 20 years by making minor modifications or updates to the original claims. The patent holder can then remove the original “technology” from the market, deeming it obsolete, and thus locking consumers into an infinite “technology treadmill” wherein they must constantly adopt the newest, patented seeds or else risk being less productive than those who do.16

From the beginning, many journalists and trade observers worried that the increased power of the seed industry to control seed reproduction would lead to consolidation, as big breeding programs could buy up or force out smaller, independent breeders, and severely curtail farmer-to-farmer seed sharing. Indeed, the companies most responsible for seeking and enforcing patents are ones with the largest percentage of market share.17 Today, just four companies control more than 60% of proprietary seeds worldwide.18,19 Because those companies with the most financial resources are able to employ both the patent writers and the lawyers to defend them, the world’s genetic resources are being locked up in the hands of just a few decision makers—a far cry from the purported purpose of patents to spur innovation and diversity. Instead, independent breeders and seed stewards find the path to new varieties, and the means for protecting existing varieties, including heirlooms and those that hold cultural importance, increasingly narrowed. In the face of climate change and extensive monocultural production within our food system, a resurgence of interest in regionally adapted and heirloom varieties of seeds has raised significant questions about who should be granted ownership of seed. Also at issue is how those who have supplied seeds, either willingly or inadvertently, to breeders can and should benefit from IPR pertaining to those seeds.

Until very recently, farmers and seed keepers were the principal producers of new crop varieties. Then, in 1990, the rediscovery and application of Mendelian genetics in 1900 catalyzed “plant breeding” as a legitimate scientific endeavor, the point at which scientists began to claim authority over crop improvement.20 However, the development and cultivation of food crops is a process, not an end result in and of itself, that has spanned the last ten millennia. As plant breeders and seed companies turn to heirloom and landrace seeds to develop new varieties, it is important to recognize the intellectual property of Indigenous seed keepers who developed those varieties through generations of careful selection.

National Plant Germplasm System and the Public Domain

When European colonists first arrived in the present-day United States, a vast and diverse system of Indigenous agriculture was already present on the continent. For several subsequent centuries, the exchange of seeds between Indigenous growers and settler communities depended largely on the individual.21 Around the turn of the 20th century, the United States government initiated a number of formal programs to support the expansion of settler-colonial agriculture in the United States.22 This initiative was supported by several congressional acts, including the Morrill Act of 1862 and the Hatch Act of 1887, which established the Land Grant University system and its attendant agricultural research mandate. In the late 19th century, every state in the country was given 30,000 acres of federally controlled land, with which they could fund or endow public institutions whose designated mission would be to study agriculture, science, and engineering. Of course, the transfer of “ownership” from the federal government to the states necessitated the violent dispossession of nearly 11 million acres of Indigenous land.23 This was only one instance of the US government claiming Indigenous resources as part of the country’s supposed public domain.

The turn of the century also brought with it the development of the USDA Section of Seed and Plant Introduction, whose purpose was “to bring into this country for experimental purposes any foreign seeds and plants which might give promise of increasing the value and variety of our agricultural resources.”24 Through this process, plant varieties that had been developed over thousands of years through traditional breeding methods were claimed as “public domain” for the advancement of colonial science, reflecting the dominant global intellectual property structure in which people of color produce raw materials and white researchers “refine” it for sale.25 Since 1898, the US has acquired over 600,000 different plant accessions from seed growers all over the world, representing 14,208 species, including “nearly all of the crops of importance and interest to US agriculture.”26 Today, this collection is housed under the National Plant Germplasm System (NPGS), whose stated mission is to “safeguard and utilize plant germplasm (genetic raw material), associated genetic and genomic databases, and bioinformatic tools to ensure an abundant, safe, and inexpensive supply of food, feed, fiber, ornamentals, and industrial products for the United States and other nations.”27 The NPGS is a critical source of germplasm for nearly all plant breeders in the US.

The USDA-ARS GRIN

The NPGS is managed by a computer database called the Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). The GRIN allows users to search available accessions by name, country of origin, or traits mentioned in the accession description. Anyone can access seeds from the GRIN for free, so long as they are requested for bona fide research or education purposes. According to the US National Plant Germplasm System Distribution Policy, seeds from the GRIN can be used for variety trials and breeding projects that might result in a marketable product, but cannot be marketed themselves, used for home gardening, or requested for any purpose that might directly compete with commercial seed producers.28 Because the 21st century has been marked by increased privatization of seed in the United States and a dramatic loss of diversity in favor of high-yielding monoculture—an unfortunate consequence of its own invention—the GRIN is an important repository for plant genetic diversity, preserving seeds that would have otherwise been lost to industrialization. OSA’s 2022 State of Organic Seed reports that the GRIN is the single most important source of germplasm for public breeding projects.29 The collection also houses, albeit ex situ, culturally important seeds for Indigenous communities that have otherwise been dispossessed of their land and cultural resources.30 Despite its usefulness, a problem of concern is that the varieties that result from breeding projects that use GRIN accessions can then be patented in a colonial process that effectively created a “public domain” and then closed the doors to any derived benefits behind them. Plant breeders who access the GRIN should remember that seeds in this collection were obtained during a century that unilaterally disregarded the intellectual property rights of the communities from which they originated. In the next chapter, we elaborate upon these and other issues inherent to the current patent system for seeds.

CHAPTER 2: What’s Wrong with Patents on Seed?

What is a Utility Patent?

A patent is a right that is conferred upon an inventor that grants them exclusive commercial rights to produce and use the new technology. There are three different types of patents granted by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO): design patents, plant patents, and utility patents.32 While design patents only pertain to the ornamental aspects of an invention and not their function, and plant patents only refer to asexually reproducing, non-tuberous plants, utility patents can claim “anything man-made under the sun.” About 90% of all documents published by the USPTO are utility patents.33

To satisfy the requirements of a utility patent, the invention in question must demonstrate the following:34

Subject matter: “Any process, machine, or composition of matter, or improvement thereof” (35 U.S.C. § 101).

Novelty: The invention is not already described in a printed or online publication, offered for sale, or demonstrated publicly (§ 102).

Non-obviousness: The invention is not “obvious” when existing prior art is combined (§ 103).

Enabling disclosure: The invention is described in sufficient detail to allow a person reasonably skilled in the art to recreate the breeding process.

In the case of utility patents on plant varieties or their traits, especially those that have been traditionally bred, the question of novelty or non-obviousness is not always cut-and-dry.

Both claims involve a search for prior art. Prior art is evidence that the invention in question does not already exist or is not the obvious outcome of combining inventions that already exist. Plants that exist in nature can be considered prior art, as can traditional knowledge of a plant or its uses. Written records of an invention’s existence, such as sales receipts, blog posts, forums, podcasts, news articles, and journals articles can also be included in the scope of a prior art search. Proving the true novelty of a plant or genetic trait is a task that, if performed thoroughly, would necessitate innumerable queries of nature and literature.

Discovering a gene isn’t the same thing as an invention. I think we need to break that down in the mentality of the nation and the world. Plant breeders are not inventors. They are noticers of observable phenomena.

–Tessa Peters, The Land Institute

Utility Patents Pose Challenges to Breeders and Growers

Theoretically, the purpose of the patent system is to encourage competition and innovation in the marketplace. However, plants do not fit perfectly into a system designed to protect inventions for several reasons. First, unlike true inventions, new plant varieties are not engineered from scratch; like humans, they are the living result of millions of years of continued adaptation to their environment. Even the introduction of genetic engineering techniques are limited to material already found within the biological genome. Second, seed-bearing plants reproduce naturally and require no capital input to do so. Unlike a car or a computer, the person who holds one seed can soon hold thousands, a capacity that inherently defies the aim of the patent system, which is to restrict the reproduction of an invention to the person who originated it. Finally, the patent system expressly requires an “enabling disclosure.” This requirement becomes particularly clouded over when companies exclusively cite proprietary inbred lines, or otherwise obscure the breeding history of a variety by referring to its predecessors by number rather than name.35 Without a description that truly “enables” the public, patented seeds and their traits become siloed off from the rest of the seed pool, restricting the exchange of seeds that produces the wide diversity and regionally adapted crops humans have enjoyed for thousands of years.

Twice Congress developed specific intellectual property protections that acknowledged these inherent incongruities and created alternatives to the patent system: first with the passage of the Plant Patent Act and then the Plant Variety Protection Act. The PPA only covers asexually reproducing plants, and the PVPA expressly permits farmers to save seed for on-farm use and breeders to use seed for research and breeding. When Diamond v. Chakrabarty endorsed the application of utility patents to a genetically engineered bacterium, a decision that quickly was applied to plants and their progeny, genetically engineered or not, the court blatantly disregarded and overruled Congress’ previous acknowledgment that seed-bearing plants are not suitable for intellectual property claims under the patent system.

In the years following the 1980 Diamond v. Chakrabarty decision, utility patents on plants have been used as a mechanism to fuel the consolidation of power in the seed industry, a phenomenon that has resulted in an erosion of genetic diversity and a disregard for traits essential to a sustainable food system, especially for staple crops like corn and soybeans, where IPR-protected varieties make up a majority of the marketplace.36 As corporations consolidate and their direction becomes increasingly driven by shareholders, traits that prioritize taste, nutrition, resilience, and soil health are lost to those that increase profits—traits like uniformity and high yield.37, 38 Seed companies use genetic engineering to prioritize resistance to herbicides and other pesticides, which are often patented and marketed by the same companies that sell the seeds that depend on them. Patents are also used as a lever to pry important genetic and cultural heritage from communities, often in direct violation of patent law’s novelty and non-obviousness requirements, a form of cultural violence known as biopiracy.

What is Biopiracy?

As discussed in Chapter 1, the current political and economic structure of the United States commodifies knowledge through intellectual property policies that are complex, expensive, and reward only a narrow definition of “innovation”—a definition that falls within the constraints of Western science.39 Under a systemic colonial regime, intellectual property rights are used to “expropriate knowledge” and define a category of people as “nonexperts, especially people of color” who are excluded from being considered legitimate holders of intellectual property.40, 41 The privatization of Indigenous knowledge is also known as biopiracy, or bioprospecting. Indian seed advocate Vandana Shiva has written extensively about colonial theft of plant varieties, such as the RiceTec, Inc. patent awarded for basmati rice and the W.R. Grace patent on neem, a natural pesticide, both of which have been used in Indian agriculture for thousands of years. These patents curtail the ability of the Indian people to control the sale of their own plant material.42 Domestically, in 1999, Nor-Cal, Inc. received a patent on an improved variety of wild rice, a diet staple for the Ojibwe people in Minnesota.43 Indigenous activist Winona LaDuke asserts that such patents constitute a threat to the tribe’s ability to control their food system, as cross-contamination of patented varieties could prevent the Ojibwe from their traditional harvests.44 These examples show that utility patents can be used to legally reinforce colonial oppression.

Further, Indigenous knowledge typically considers seeds to be living relatives, and while Indigenous cosmologies are not monolithic, many tribes believe that seeds are not to be owned, sold, or commodified. This poses an additional paradox in which keepers of traditional agricultural varieties might have to choose between claiming “ownership” and restricting access to seed to prevent a foreign entity from doing so first. Andrea Carter, a member of the Powhatan Renape Nation and Agricultural Outreach and Education Manager for Native Seeds/ SEARCH, has described the double bind in this way: “It’s almost a different perspective that you have to take on: the colonized way of thinking that you can own the seed to protect your seed. What’s tricky is that it’s antithetical to a traditional or Indigenous way of looking at seed of any life, but it might be necessary for protecting it.”

For this and other reasons, chief among them that it is unethical to claim ownership of life, and that patents allow their owners to claim “ownership” of seeds by restricting others from saving them, Organic Seed Alliance does not support the utility patenting of seeds, plants, and genetic traits. Other forms of IPR are more suitable for providing protections and royalties to developers of varieties. In other words: Utility patents are the wrong tool for “protecting” seed. Indeed, the consequence of utility patents is quite the opposite—utility patents put the diversity and viability of our seed commons, and our ability to co-evolve with our food crops, at risk.

Breeding Considerations for Indigenous and Culturally Important Seeds with Noah Schlager

When preserving Indigenous seed varieties, a grower who is not a member of the originating community must understand that there are protocols about how Indigenous varieties are meant to be maintained. Noah Schlager, a seed keeper of Mvskoke-Creek and Catawba heritage and the former conservation program manager of Native Seeds/ SEARCH (NS/S), presented on this topic during the Organic Seed Alliance “Organic Seed Production” course in 2021.

In the case of Indigenous corns, he noted, collections like those held by NS/S and other preservationists contain some of the very last deeply original corns to Indigenous communities, and that means that oftentimes they were some of the most sacred. Preserving the identity of those varieties requires deep conversation with traditional seed keepers and understanding of the spiritual significance of the variety and its phenotypes. Even roguing what may be seen by an outsider as an “offtype” could lead to the loss of traits that make up the identity of a particular variety of corn.

“For example,” said Schlager, “a lot of Native American corns will occasionally have white or albino seedlings that come up and then disappear. They’re going to die away. That’s sort of their role. They’re a short visitor and they go back. But from just a pure productivity mindset for someone who doesn’t have any connection or understanding of the culture, they might just say “Oh, that’s just kind of a dud. I want to breed that out of this variety so that it doesn’t happen anymore.” I think it’s really worth stopping and thinking about who we need to include in the conversations whenever we’re selecting corn. And to remember that for a lot of Indigenous people, just productivity or just that one particular kind of trait is not the thing that is most important about a variety. Oftentimes, it’s the fact that our ancestors held these seeds, and that they have spiritual values to us, and that they have cultural values and they’re meant for particular kinds of food.”

As settler seed growers began using Indigenous corn, they did away with traits that inhibited productivity or the ability to mill and process corn, even though those traits might have added diversity and resilience to a population. “And now those traits are incredibly rare,” Schlager said, “and we have to work to revitalize those varieties.”

He recognized that even planting seeds in different climatic conditions or soils is a form of selection, and that the location of a grow-out should be chosen with those factors in mind. “We have to think about the best place for these varieties to maintain the traits we want to see.” Without those considerations, the seeds could quickly change into varieties that are significantly different from those that were bred for a specific place and community context.

For example, many seed companies advertise “Hopi” corn. The Hopi, who live in the northeastern corner of Arizona, are foremost among Native American farmers in the United States in retaining their Indigenous agriculture and folk crop varieties, using the same farming method they have for over 2,000 years. Their corn is adapted to have an incredibly deep taproot to take advantage of winter moisture and short stature that protects them against the harsh winds of the desert.45,46 Growing Hopi corn in any other context, even for a couple of generations, reduces the selective pressure of those environments. Further, Schlager said, “you don’t have the attention and care and stewardship of Hopi seed keepers who know what they’re looking for.” Grown outside of the Hopi community, the corn is no longer “Hopi corn.”

He explained that there are seeds that grow in specific places, or even specific hillsides that, from an Indigenous perspective, don’t make sense outside of context. And then there are other seeds that are more general, or were intended for trading, or are for a lot of different contexts. “And those we can see more easily fitting into something like a breeding project,” Schlager added.

Still, even choosing not to select for any particular characteristics, in an attempt to retain the identity of the seed when it was collected, is an active decision in and of itself. “The very act of growing these seeds is going to change them. These are living things—they evolve. They have always been selected, and they will continue to adapt.” Decisions about where and how to grow Indigenous varieties should be made in collaboration with Indigenous seed keepers, he said. “We have to care about these seeds and keep them alive and also to care about equity and fairness for farmers who haven’t had their voices uplifted in this conversation.

Why Do Some Companies Patent Seeds They Don’t Plan to Defend?

Although the express aim of the utility patent system is to allow the inventor of a product to establish market presence by restricting its use by others, some seed companies that hold utility patents on seeds would not be averse to other breeders using that material, according to breeders interviewed for this resource. Instead, a major reason why some seed companies patent seeds is to simply increase the value of their portfolio. If one company is using exclusive access to quality germplasm to increase the value of their brand, other companies have to follow suit to remain competitive. For example, Emily Rose Haga, a former breeder for Johnny’s Selected Seeds and the former executive director of Seed Savers Exchange, said that she has been told that some companies will patent seeds to show value to shareholders.

“It’s a way to say look at us, we’re innovating. We’re ahead of the curve. Whereas they don’t intend that not to be useful to another plant breeder, or maybe they’re willing to share it, but with royalties,” she said. For this reason, it is worth contacting a breeder or patent holder directly to ask about using their seeds in a breeding project. Indeed, Haga added, another reason she’s heard some breeders apply for patents is not to restrict their use at all, but rather to prevent someone who would from patenting the variety or trait first. “It’s sort of a mind twist, saying, well, I’m going to seek intellectual property rights so that somebody else doesn’t seek the intellectual property rights and prevent other people from using this…It’s just kind of an example of where we’re at as a seed community.”

Seed companies also use patents as bargaining tools to access other patented material. Adrienne Shelton, a plant breeder for Enza Zaden, describes the negotiation:

As a lettuce breeding company, there are a couple of disease resistances that have to be in our varieties in order for our growers to be successful. One of them is downy mildew resistance, of course, which continues to be a problem. And then another important resistance is Nasonovia (aphid) resistance. One of the reasons that we are patenting our varieties is that our competitor company Rijk Zwaan, who also develops lettuce, has patents on Nasonovia resistance.

Adrienne said Enza Zaden agreed to trade their patent for downy mildew resistance to Rijk Zwaan in exchange for access to their Nasonovia-resistance trait. “Because we had a patent and they had a patent, we then essentially agreed to share,” she said. “So all of Rijk Zwaan varieties have the full downy mildew resistance and Nasonovia resistance and most of ours have both of them as well, even though we don’t have the patent for one of those. Without those resistances, we can’t compete in the large lettuce market in California.” By obtaining the patent on a desirable trait, Enza Zaden was able to leverage their access to “unlock” other essential traits for their breeding work. In some ways, this exchange highlights the inability of the patent system to promote innovation; instead, it forces companies with adequate resources to buy in and excludes the rest.

Can I Get Sued for Growing Patented Seeds?

Restricting access to seeds is one way the patent system works to narrow crop genetic diversity. Ironically, patented seed also has the potential to inadvertently contaminate farmers’ varieties whose traits are carefully preserved and whose growers do not have the financial resources to defend against accusations of patent violations. Several seed growers interviewed for this resource, especially those who work with Indigenous, local, or culturally important varieties specifically mentioned not being as much concerned about the patenting of their varieties by other seed growers, but rather of genetically engineered and patented traits contaminating their culturally important crops through cross-pollination and genetic drift.

It seems unlikely, despite a persistent myth to the contrary, that a farmer could be legally liable for growing patented seed due to accidental contamination, or “genetic drift.” In 1998, Monsanto famously sued Canadian farmer Percy Schmeiser for growing Roundup Ready® canola in his field, which Schmeiser claimed had drifted onto his fields by accident. However, the court eventually determined that Schmeiser had intentionally selected for the Roundup Ready® trait, which may have indeed drifted into his fields through cross-pollination, by spraying his entire field with the herbicide, saving seeds from the plants that exhibited the resistant trait, and planting the resistant seeds the following season. The court ruled that Schmeiser was guilty of patent infringement; however, he was not made to pay any form of restitution, as Schmeiser had not sprayed the second-generation crop with Roundup and Monsanto could not prove that he had financially benefited from growing canola with the patented trait. It could be argued that Schmeiser should have been ethically permitted to save and grow whichever seeds he so chose; legally he was prohibited from knowingly saving and growing seeds with patented traits.47 At the time of the trial, Monsanto had publicly committed to never “exercise its patent rights where trace amounts of [its] patented seeds or traits are present in a farmer’s field as a result of inadvertent means.”48

Still, this assurance does little to resolve the very real concern that patented GE seeds might incidentally contaminate culturally important crops, thus altering their composition in detrimental ways. One Indigenous grower interviewed said:

I am very concerned. I’m very concerned, because I have a feeling that there are elements of ancestral varieties of seed that are already within patented seed, and that if some of the seed that I’ve grown with was tested, it would have trace amounts of that even though the engineered seed came from, you know, that particular ancestral variety.

I know this one grower in particular, whenever he sees a different color pollen, or a different color expressed within his corn, he immediately plucks it out and burns it. We also shouldn’t have to do that. Because even though that particular trait is expressing itself, there’s still ties to our ancestral seed within that same kernel. So it’s hard and heartbreaking.

In an interview, traditional seed grower Stevan de la Rosa Tames, who grows in a rural community in Sonora, Mexico, mentioned that his isolation from other seed growers has largely served to protect the varieties he keeps from cross-contamination by genetically engineered traits; however, that isolation also means losing potential diversity:

I feel spoiled or privileged or lucky in that I landed in the place that I did. At least I see it that way because I don’t have to deal with big ag contaminating me in different ways. The nearest industrial agriculture is a six-hour drive from here. My neighbors are not all growing similar stuff that could get crossbred. And I mean, it’s good for keeping the seeds that I’m growing pure, but I know that I’m also losing out on other seeds that my neighbors might be able to have, on having that community to do it in, which would enrich the whole process.

So while Monsanto might not sue growers who are found to have incidentally contaminated crops, the burden of avoiding cross-contamination still creates undue consequences for seed growers.

There might not be evidence that Monsanto would sue farmers for trace amounts of inadvertent GE contamination; however, the company has a long track record of suing farmers for patent infringement using tactics that many deem invasive and coercive. According to the Center for Food Safety, “As of December 2012, Monsanto had filed 142 alleged seed patent infringement lawsuits involving 410 farmers and 56 small farm businesses in 27 states,” resulting in awarded sums that totaled over $23 million.49 In 2018, German chemical and pharmaceutical company Bayer acquired Monsanto, the massive value of the company and its patents further fueling consolidation of power in the seed industry.50 While to our knowledge, there have not been recent reports on the number of patent lawsuits from the company post-merger, it is reasonable to assume that the conglomerate still pursues investigations on potential patent infringements. Fliers recently published by Bayer include language that encourages farmers to anonymously report “potential seed compliance matters.” It is also probable that during the height of its litigations, Monsanto was attempting to publicly demonstrate the consequence of saving seed in violation of patent laws while the extent to which they could be defended was still unsettled. Over 20 years have passed since the Schmeiser case, and the courts since have affirmed the power of patents to restrict seed-saving practices. Perhaps any conventional farmers who were once accustomed to doing so have now been soundly dissuaded.

More recently, German chemical company Badische Anilin und Soda Fabrik (BASF) sent out a letter to regional seed companies in the United States that made broad claims about plant varieties and genetic traits covered by their patents. Titles for the patents listed included “drought tolerant plants,” “onions with high storage ability,” and “seedless fruit producing plants.” The letter warned recipients, some of whom had never even purchased BASF seed, that the unauthorized use of “germplasm covered by one or more of claims” would be a violation of its intellectual property rights. Further, the letter claims that using the traits in the listed pending patent applications would be a violation of the company’s IPR, which is untrue as patent applications are not defensible until they are granted. The letter used this assertion to encourage seed companies interested in germplasm listed to request non-exclusive licenses in order to use the claimed technology.

It seems that the goal of the letter, which BASF affirmed it sends annually to a “large number of US seed companies,” is not necessarily to prosecute seed producers who may be growing plants with the referenced traits. Instead, it seems aimed preemptively at intimidating small seed producers away from seeds and traits over which they claim ownership—a much less expensive endeavor than enforcing patent compliance through litigation.51

GMOs and Patents

There is a persistent misunderstanding that patented seeds are always also genetically engineered. While it’s true that many genetically engineered (GE) seeds are patented, not all patented seeds are GE. In fact, many existing utility patents on seeds and their traits are on seeds bred using traditional methods. The difference is significant. In traditional plant breeding, new varieties are made by cross-pollinating plants with different traits and selecting offspring that demonstrate the most desirable characteristics. Cross-pollination is often done by hand, by painstakingly transferring pollen from one individual—using toothbrushes or tweezers—to the pistil of another. Because this involves rearranging thousands of genes with each cross, as in natural reproduction, traditional plant breeding methods can take years to create a new and stable variety. By contrast, genetic engineering allows breeders to alter, remove, and/or insert single genes using molecular “scissors.”52 While parents in traditional breeding must be closely related enough to naturally reproduce, genes used in genetic engineering are not bound by the constraints of biology and can be introduced across species and even across kingdoms. Perhaps the most famous example of genetic engineering is Bt sweet corn, in which an insecticidal protein (Bacillus thuringiensis) commonly found in soil bacteria has been inserted into the corn genome to create varieties that naturally produce the protein themselves. Today, about 83% of corn grown in the United States contains the Bt gene.53 Many of the methods that produce GE corn, and many of the individual traits, are covered by patents. Because corn is a notoriously promiscuous cross-pollinating crop, this has led to significant disputes about the ability for GE and patented traits to inadvertently pollinate neighboring, non-GE corn crops.54

How Do Problematic Patents Get Granted?

If patent applications have to go through a vetting process that includes a search for existing similar inventions, the question arises: How do patents on traditionally bred crops, whose lineage comes from the public domain and whose traits are already well-documented, get patented in the first place? Although the patent review is a formalized process, it is still conducted by humans and is subject, largely, to human discretion.

When a patent application arrives at the USPTO, it is delivered to one of nine Technology Centers, each of which specializes in reviewing applications relating to specific subjects. Each Technology Center is further divided into Groups, which are then divided into Art Units, which consist of about 12 patent examiners each. Group 1660, for example, deals with “Plants” and “Multicellular living organisms and unmodified parts thereof and related processes.” Patent examiners (PEs) usually have an advanced degree in the field pertaining to their specific art unit. Once a patent application has been assigned to a particular patent examiner, they design the prior art search, which might include consulting other patent examiners or staff at the Scientific and Technical Information Center, a library like resource that can help patent examiners locate examples of prior art. According to the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure, each patent examiner must search domestic patent databases, foreign databases, and non-patent literature (which can include journals, internet searching, and even social media posts) to determine whether the invention in question is truly novel and nonobvious.55 Still, each patent examiner develops their own process for conducting the prior art search, and there is no list of required resources the patent examiners must search in each examination. Instead, the comprehensiveness of the prior art search varies highly depending on the patent examiner conducting the search.

As noted in Chapter 4, designing a prior art search that adequately investigates all possible avenues for evidence of a plant or trait’s existence is, at the outset, perhaps an impossible task. In addition, the patent office is consistently backlogged in such a way that patent examiners are incentivized by the number of applications they are able to process. On average, a patent examiner spends only 19 hours reviewing a patent application, including the search for prior art.56 More experienced examiners spend less time on each patent; each job promotion for a patent examiner results in a 10-15% decrease in the number of hours the USPTO allocates them per application.57 Perhaps as a result, examiners with more experience tend to cite fewer instances of prior art in the application review process. They are also more likely to grant patents.58 In sum, examiners are rewarded for spending less time on the patent review process, resulting in less comprehensive reviews of prior art.

The Patent Backlog

While there are standards in place that should ensure a patent examiner captures all relevant literature in a search for prior art, the reality is that patent examiners have an overwhelming backlog that limits the amount of time an examiner can spend on each application. Between 2000 and 2020, the number of utility patent applications to the USPTO per year doubled from 295,926 to 597,175.59 As of December 2021, there were over 666,000 patent applications awaiting review by a patent office.60

Further, because the USPTO is a fee-based agency that depends on application and patent renewal fees to generate revenue, and because patent applications are increasing every year, it is likely that the office will be underfunded so long as application trends continue, resulting in a continual backlog that degrades the quality of the patent review process and results in the routine issue of bad patents.61 Paulina Borrego, a patent librarian at the University of Massachusetts Amherst Patent and Trademark Patent and Trademark Resource Center, underscored this fact when asked how patent examiners conduct their search: “It’s a 100% fee-funded agency. So everything [the USPTO does] is based on churning out patents and making their workflow easier.”

Because there are incentives for the number of patents an examiner can process, prior art may be and is often overlooked, especially when published in a medium unfamiliar to patent examiners.62 In fact, previously published patent applications account for the majority of prior art referenced by both applicants and examiners. In 2018, the USPTO launched the “Access to Relevant Prior Art Initiative,” which was intended to streamline the prior art search process for patent examiners. In 2020, the agency also launched a beta version of an artificial intelligence tool called “Unity” that would allow patent examiners to conduct more comprehensive searches for prior art across patents, publications, and non-patent literature.63 The USPTO states that these efforts are intended to alleviate the backlog of unexamined patents, as well as to ensure that the most relevant prior art is located at the beginning of the patent examination process. Whether or not these programs achieve those goals is yet to be seen.

Seed Stories: Downy Mildew Cucurbits

Downy mildew is a highly infectious pathogen that affects nearly all broad-leaved crops. The water mold thrives in moist or humid conditions and spreads on air currents before making its way to plants, splashing in water and moving quickly throughout a field. It can cause leaves to turn brown or curl inward and causes significant damage to crops every year, especially in cucurbits, resulting in millions of dollars of crop loss.

Almost 15 years ago, Edmund Frost became the farm manager of Twin Oaks Community Seed Farm in Louisa, Virginia. Since then, Frost said, “Cucurbit downy mildew has been the number one limiting factor in cucurbit production” at their farm. Inspired to find varieties resistant to the pathogen, Frost applied for his first SARE grant in 2013 in order to perform variety trials in search of cucurbits with downy mildew resistance.

Breeders have long known about accessions in the USDA-GRIN system that demonstrate resistance to cucurbit downy mildew, one of the most well-known being a semi wild relative, called accession PI197087, noted in trails going back as far as the 1980s. However, as the genes for the pathogen began to adapt, the resistance in that particular accession proved less and less effective. In 2004, varieties of cucurbits that had, until then, resisted downy mildew finally succumbed, and growers from Florida to Maryland had their fields devastated by the disease.64 Thomas Joyner, the president of a cucumber processing facility described the severity of the situation to NPR: “The crop almost melted,” he said. “There was almost nothing left.”65

When Edmund Frost began his variety trials, he needed a different source for the trait, one that was still working against downy mildew. He wrote to Michael Mazourek, a prominent vegetable breeder at Cornell, who had worked as an advisor to Frost’s breeding work. He sent along 197088, which seemed to still show the resistance, for inclusion in the variety trials at Twin Oaks.

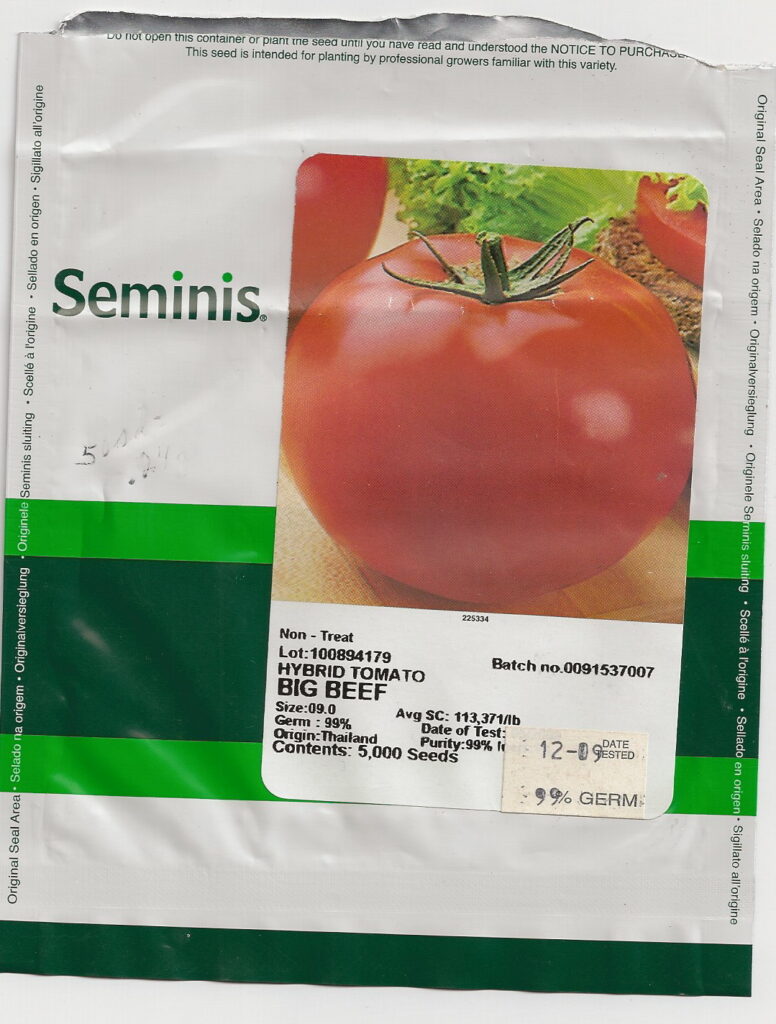

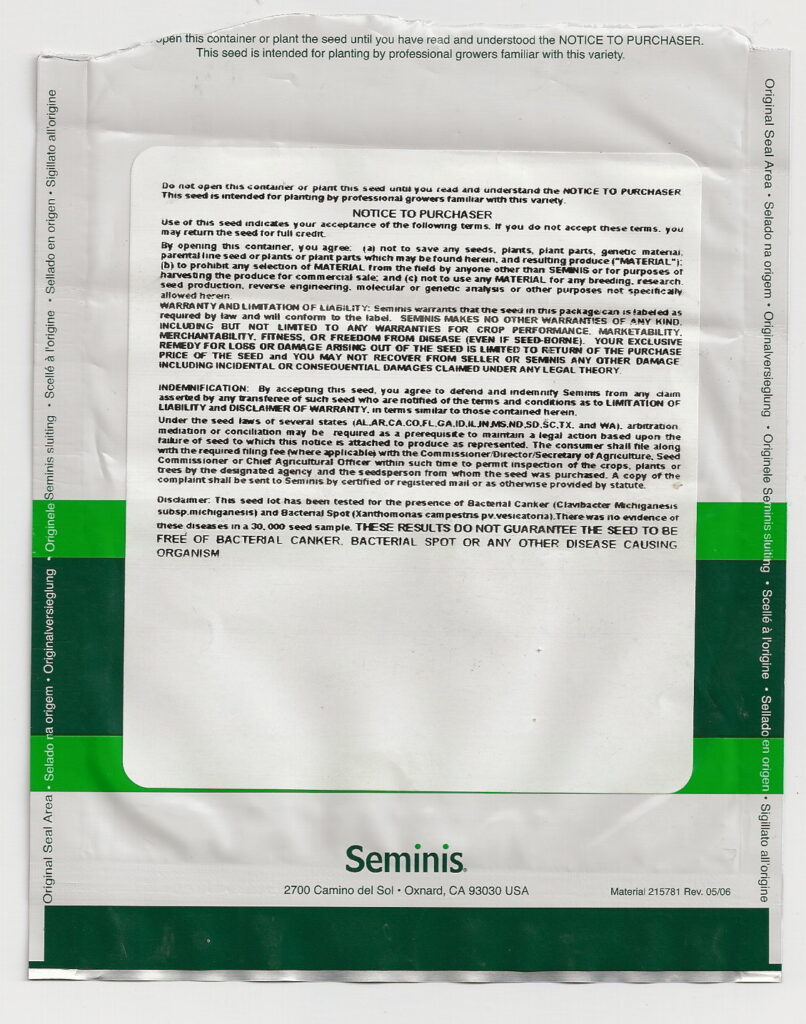

Three years later, Seminis Seeds applied for a patent that claims downy mildew resistant cucumbers whose resistance is derived from PI197088, the same variety Frost was using in his trials. In 2017, the patent was granted.

“It’s just a ridiculous overreach,” Frost says. “It already is a cucumber and it’s a cucumber that somebody else developed and they’re saying you can’t use it to make a cucumber.” It’s a claim he doesn’t think would hold up in court. “At the time,” he added, “I was interested in trying to figure out a way to put it out there, like, hey we’re using this. What are you going to do about it? And trying to instigate a trial.”

Frost says he didn’t end up using PI197088 in his breeding lines, ultimately because it ended up having susceptibility to another pathogen, bacterial wilt. He is, however, continuing to develop other downy mildew resistant cucurbits, including a cantaloupe, a Halloween pumpkin, and South Anna Butternut squash, a variety he released with the OSSI pledge in 2016. He says that graduate students in Michael Mazourek’s breeding program at Cornell were using the downy mildew resistant variety, and ended up discontinuing their project after the Seminis patent came out.

This isn’t the first time a patent like this has shut down a breeding project, especially at public institutions whose approach to intellectual property is more measured. Irwin Goldman, a professor at the University of Wisconsin, shelved a 15-year breeding project for red carrots after Seminis applied for a patent for “carrots with increased lycopene content.” Jim Myers, a breeder at Oregon State University, was teaching a student how to search the patent database when he came across a patent for Northern-adapted nuñas, a type of popping bean common to the Andes. Myers had been working with breeders at Colorado State University and University of Wisconsin on a northern-adapted nuña for years, but all three breeding programs promptly shelved their project when they came across the patent. Neither the university, nor the company that held the patent, ever released the bean for commercial use.

Notably, one of the people I talked to for this resource have actually been prosecuted for infringing on a patent during a breeding project. A popular theory is that because these patents wouldn’t hold up if challenged, the companies who hold them have to protect their claims through intimidation alone.

How Do I Know if My Seed is Patented?

Until recently, the only way to access the USPTO database directly was to use its legacy search system, the USPTO Patent Full-text and Image Database (PatFT); however, the PatFT was notoriously difficult to navigate and posed a barrier for seed growers who wanted to know how patents affected the crop they worked with. In fact, even many patent librarians opted instead to use the European database Espacenet, which has better search functions and an easier-to-navigate user interface. Patent databases around the world often list patents that have been granted by other countries’ issuing offices, and individual foreign patents are searchable by their “country code,” which precedes the patent number. Today, for most cursory patent searches, Google Patents is the simplest way to determine if a variety or trait has been patented.

Google Patents allows someone to search by keywords as well as by inventor name. Yet, keep in mind that even if the variety doesn’t appear on an initial search, it still might be under patent protection. For example, although Aerostar lettuce was released by Vitalis Organic Seeds, a search for “Vitalis” returns no results; instead, the patent’s inventor is listed as Monia Skrsyniarz, and the assignee is Enza Zaden. A patent assignee is an individual or company who has ownership interest in a patent. In this case, Enza Zaden owns Vitalis Organic Seeds, so Enza Zaden is the patent’s assignee. Due to the current rate of consolidation in the seed industry, it is sometimes difficult to ascertain whether the seed sold by one company is actually owned or patented by a larger, parent corporation. For this reason, it is also challenging to aggregate data on the number of patents that are held by specific companies or by specific breeders.

To search for all new or pending patents of a specific crop type, it is also possible to search patents by their Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC).66 The CPC was developed jointly by the USPTO and the European Patent Office. The CPC system divides subject matter into nine sections denoted by the letters A-H (and Y for emerging technologies), which are then further divided into classes, subclasses, groups, and subgroups. The proper nomenclature for new seed-bearing plants for example is “A01H 5/ and 6/.” In this case, Section A refers to Agriculture, which is further divided into Class 01, for all utility patents relating to agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, hunting, trapping, and fishing. Subclass H houses all patents relating to “new plants or non-transgenic processes for obtaining them.” Groups 5/ and 6/ refer to angiosperms, i.e. flowering plants, which are classified in group A01H 6/00 according to their botanic taxonomy and in group A01H 5/00 according to their plant parts. To find all utility patents on carrots, then, one could search by the CPC “A01H 6/068.” In 2022, the USPTO launched a new online search tool called PubSearch, designed to replace the legacy PatFT and its counterpart for pre-grant applications (AppFT). The new PubSearch tool allows users to search both newly-granted patents (issued every Tuesday) as well as patents that are still in the pre-grant phase (issued every Thursday). Searchers can search by CPC, inventor, or other keywords. Searching by crop type could be useful for plant breeders or seed growers who work with a specific crop and would like to monitor new patents that might affect breeding projects. For more information on how this information could be used to prevent or challenge future patents, see the next chapter.

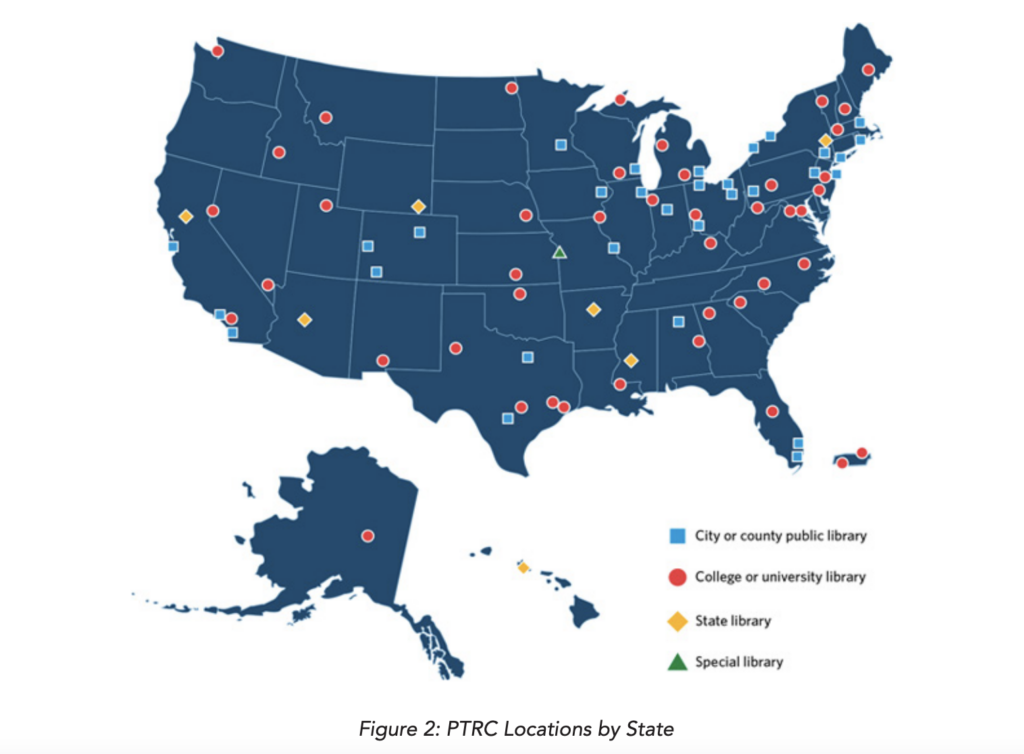

Resources Available Through the PTRC

Given how challenging it can be to navigate the patent search and application process, the USPTO created Patent and Trademark Resource Center (PTRC). The PTRC is a network of libraries designated by the USPTO to help distribute patent information and support public intellectual property needs. The PTRC has over 80 member branches in libraries around the country, most of which are housed in public or university libraries (see Figure 2: PTRC Locations by State). All are staffed by librarians who are trained in patent searches and have access to proprietary, examiner-based databases. PTRC librarians can help members of the public search for existing patents on plant varieties or genetic traits. They can also provide support during the application process for trademarks and patents. Anyone can consult with a PTRC librarian, usually by making an appointment online. Since the PTRC is a network of libraries, librarians can also help direct specific questions to other PTRC branches who specialize in more specific topics. In addition to PTRC libraries, the US Patent and Trademark Office also offers a Patent Pro Bono Program, which helps connect low-income inventors with volunteer patent professionals who can help with the patent application process. To qualify for the Patent Pro Bono Program, one must meet certain income requirements and have either completed an online patent system training course or have already submitted a provisional patent application.

CHAPTER THREE: How Can I Prove My Seed Exists?

What is a Defensive Publication?

Understanding how to navigate the USPTO can help seed growers and plant breeders protect existing seeds and challenge patent claims based on prior art. Seed stewards can establish their varieties as prior art in the public domain by creating what’s called a “defensive publication.” The goal of this strategy is to invalidate the “novelty” claims of a patent application by publicly documenting proof that a variety and its traits already exist.

In 2019, Vermont Law School researchers Cydnee Bence and Emily Spiegel published A Breed Apart: The Plant Breeder’s Guide to Preventing Patents through Defensive Publication. According to the guide, which is incredibly comprehensive, a defensive publication only requires that a person document their invention in a “physically accessible document that has been widely disseminated.”67 This means that anyone with knowledge of a novel variety and the means to document and publish prior art could put that variety in the public domain. If the claimed invention was in public use, or described in a printed publication before the filing date of the patent application, the application’s claim would be invalid. This is a crucial strategy, especially for seed growers in countries and cultures that have little interest in positively protecting their plant varieties through other, more formal protections, or do not have the financial resources to apply for and maintain them.68

The practical ability of a defensive publication to prevent someone from patenting a plant variety, however, is not guaranteed. For starters, a patent examiner reviewing a plant patent application would have to be able to actually find the defensive publication before the patent is awarded, an event not guaranteed given the immense scope of material that would need to be included in an effective search for prior art. Often, the only defensive publications usually noted by patent examiners are disclosed by the applicants themselves who are legally required to document instances of prior art they are aware of, but have no incentive for searching them out.69 In addition, for the publication to be considered prior art, every element of the application’s claim must be captured in a single publication.

In addition, the publication must be enabling; in other words, it must include a description of the method for producing the variety as specific as that which is claimed in the patent application. For example, if the application claims the crossing of two specific parent lines, the defensive publication must include the same. If the claim is so broad as to describe any plant displaying a certain phenotype, then the prior art can be equally broad, including examples of plants that exist in nature. Robin Kelson, an intellectual property attorney and the founder of the Free the Seeds! fair, encourages people to be as specific as possible when crafting defensive publications. However, she acknowledged, one potential pitfall for this strategy is that for some, if the publication were to truly be “widely disseminated,” it could alert others to the existence of certain germplasm or desirable genetic crossings and explain how to replicate them. Successful defensive publication, therefore, requires the patent examiner to capture the publication in their search for prior art before a competing company can beat them to it. Still, according to A Breed Apart, a defensive publication, even if initially overlooked in the prior art search process, may be useful as evidence in a lawsuit and may protect the seed grower against allegations of patent infringement. This chapter provides a brief overview of where to find and publish defensive publications and examples of how they have been leveraged to challenge problematic patents.

Where Are Defensive Publications Published?

While a defensive publication could be published through any venue available to the public, there are certain publications that specifically register new plant varieties.

The Journal of Plant Registrations (JPR) is a peer-reviewed publication of the Crop Science Society of America. The JPR permits plant breeders to publish research describing new and novel plant varieties, as well as other innovations involving germplasm, inbred lines, and genomic populations. Varieties that are published in the JPR are often described as being “publicly released,” and the registration of plant genetic resources requires that the breeder also deposit seeds of the variety into the USDA-ARS National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation prior to publication. These seeds are generally available to the public. In 2004, the JPR updated its policy to allow registered varieties to be concurrently protected by either patents or PVP certificates so long as the material in question is available under some terms during the period of protection and that the registering authors assume responsibility for its distribution during that time.70 For example, a search of the JPR reveals that last year, plant breeders from North Dakota State University registered a new variety of black bean with bean rust resistance named “ND Twilight,” which has also been filed for PVP protection. During the first five years of its release, the breeders offer “small quantities of seed for research purposes,” which is available by contacting the corresponding author of the article. The authors simply state that if the variety is used for breeding or development purposes, “appropriate acknowledgment of the researchers and institutions responsible for development of this cultivar would be greatly appreciated.”71 Publishing in the JPR, with or without a PVP, precludes the ability to associate the variety with other forms of restrictive licenses. (See Chapter 5 for more on this.)

While the JPR does provide a platform for plant breeders and researchers to defensively publish the existence of a new or novel variety, the implied rationale for doing so is to promote their use for research by the public. In this way, perhaps the most widely referenced venue for publishing the existence of plant varieties excludes those who wish to protect their varieties as “prior art” but do not intend for the seeds to be publicly available.72 In addition, since the journal is limited only to varieties that are new or novel, seed growers who are keeping traditional varieties are not able to submit their varieties for registration, and thus, they are as yet unable to protect their varieties by defensive publication via scientific literature.

There are other examples of defensive publication databases that have made more concerted attempts to establish a variety as “prior art” without making the information available to the general public, and which accept traditional plant varieties. For example, the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (TKDL) was started in India in 2001 as a collaboration between the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research and the Ministry of Ayurveda, Yoga, Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, Sowa-Rigpa, and Homoeopathy.73 The library is intended to serve as a repository of traditional Indian knowledge, especially in relation to plants and Indian systems of medicine. According to the TKDL, the library’s intention is not to restrict access to traditional knowledge, but rather to prevent wrongful patents due to the lack of published prior art about a particular plant or knowledge of its use. Neither is the intention of the library to disseminate information about traditional knowledge to those who could appropriate or commodify its transfer or subject the library to possible misuse: the library is available only to approved international patent offices, and patent examiners who access the TKDL must sign a non-disclosure agreement and cannot reveal the contents of TKDL to any third-party unless it is necessary for the purpose of citation. At the time of this writing, the TKDL claims that 246 patent applications have either been set aside, withdrawn, or amended based on the prior art evidence present in the TKDL database.74 Other examples of traditional knowledge databases include the Peruvian Registro Público Nacional, which is not accessible to the public, and the Korean Traditional Knowledge Portal, which is.75

Over the past several years, OSA has hosted discussions about whether a “plant prior art” repository of this type would serve as a more democratic avenue for defensive publication and a means to establish plant varieties and their associated traits as prior art that might otherwise be subject to privatization and patenting. OSA’s listening sessions involved outreach to over fifty identified stakeholders, including native seed keepers and seed keeping organizations, universities, small regional seed companies, and other allied seed growers. At present, it has been determined that a repository of this kind is not in the best interest of those whom it would most directly be designed to serve. In addition to concerns about potential usurpation of the database for commercial use, other issues raised include: the time and energy maintaining the library would require; the potential for gatekeeping by whomever was conferred the task of accepting and categorizing accessions; which individuals or communities would decide if a widely important crop would be added; and the question of whether such a database would be consistently consulted by patent examiners who are already overworked. A more ontological concern is that seeds are constantly evolving, and that listing a seed in a repository would only capture a small cross section of the variety’s history and place within its environment. Many session participants felt that the amount of energy and effort required to maintain a truly representative database would be better directed toward opposing the system that would require such information to be claimed in the first place. In the words of one seed grower: