Prairie Road Organic Seed

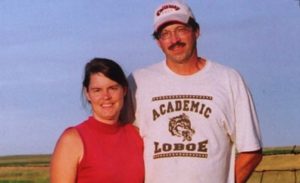

Theresa and Dan Podoll

Fullerton, North Dakota

Theresa and Dan Podoll stand out as pioneers of organic seed production in the Northern Plains. Though they describe themselves as “isolated” in their region, farming near Fullerton, North Dakota, they are intimately engaged in the national community of seed stewards through research collaborations and seed distribution.

The Podolls say relationships with national organizations inspired them to integrate seed into their farming system, pointing to their involvement with organizations like Organic Seed Alliance (OSA), Family Farmers Seed Cooperative, and the Northern Plains Sustainable Agriculture Society’s Farm Breeding Club.

“Our farm has taken part in participatory plant breeding projects, where we’re working with plant breeders and collaborators like OSA,” Theresa says. “We have also taken part in studies and working groups organized by OSA to identify and address the needs of the organic seed movement. All of these OSA endeavors have served to further network our farm and our individual efforts with that of the wider organic seed community.”

Theresa and Dan’s work with seed is best described as a commitment to the principles of diversity, health, and sustainability. Underpinning the field work is a strong sense of moral imperative.

“The changes in the seed industry since 1984, when Dan and I began farming, has been one of dramatic consolidation and monopolistic control,” Theresa explains. “This has struck a devastating blow to the biodiversity of our food and agriculture system, drastically eroding and narrowing both the diversity of species in our agricultural landscape and the genetic diversity within those species. The patenting and restrictive licensing of seed, genes, and plant breeding material has drastically eroded access to biodiversity. Our seed system is ecologically brittle. Our seed system is politically brittle.”

“These challenges present an opportunity — and as a seed steward, an imperative — to act,” she adds. “We must take the seed in hand and create alternative systems that provide for ecological, political, and economic access to biodiverse, elastic seed systems capable of adapting to a changing climate.”

Beyond organizational support and courses, the Podolls point to individuals who have strengthened their resolve to help build resilient seed systems, including Dan’s brother, David Podoll, Steve Zwinger, research agronomist at NDSU Carrington Research Extension Center and fellow organic seed producer, Matthew Dillon, co-founder of Organic Seed Alliance with John Navazio, plant breeding mentor. Raoul Robinson (Return to Resistance) and Gary Nabhan (Where Our Food Comes From, Retracing Nikolay Vavilov’s Quest to End Famine) also influenced the Podolls.

But it’s their garden, Theresa says, that David Podoll has always elevated as the teacher and focal point of their farming philosophy. The garden represents true sustainability and is the yardstick against which they measure every other enterprise on the farm.

“Seed saving, breeding, and selecting varieties well-suited to our needs for sustenance, taste, and beauty has always been an integral part of the garden,” she says.

The Podolls save seed of both horticultural and agronomic crops for their own farm’s use. They carry out variety selection and improvement work of these crops, and conduct on-farm breeding projects as well. This work formed the basis of their commercial seed production. Many of the varieties they sell commercially were bred on their farm.

“We maintain a stock seed program for all of the varieties we sell commercially, continually selecting the best for ongoing adaptation and improvement in the face of changing conditions,” Theresa says. “We are committed to the maintenance and improvement of open-pollinated varieties, empowering the selection and adaptation of varieties to the environment of their intended use.”

Some of the vegetable crops the Podolls work with include squash, pumpkins, popcorn, flint corn, watermelon, onion, peas, beans, tomatoes, beet, basil, and cilantro. Field crops include buckwheat, triticale, oats, sorghum, hairy vetch, wheat, and proso millet.

The Podolls began producing organic seed for catalog companies in 1997. They released several varieties that were bred for their own table. Becoming seed stewards, they say, has allowed them to dramatically increase the biodiversity and enterprise diversity of their farm. In 2012, they started selling retail packets of seed under their Prairie Road Organic Seed label, and have placed seed racks with retail partners in Minnesota, North Dakota, and South Dakota.

Their variety descriptions clearly convey the care and enthusiasm infused in their organic seed enterprise and the value they place on biological processes. Take a new variety in their catalogue, the ‘Dakota Bumble Bean.’

The bumblebee did it! Transferring pollen, perpetrating a cross with Jacobs Cattle bean, a bumblebee gifted us with a happy anomaly! After a few years of planting, observing and enjoying this gift, we decided we should share it with you and give credit where credit is due! Enjoy natures bumble-ly diversity!

Consider, too, that when asked if she had a favorite plant variety, Theresa responded in laughter: “That’s like asking if you have a favorite child!”

She goes on to say, “When the first harvest fruits of each one of our crop varieties is ripe and ready to eat, there is rejoicing! I can truly say that all of our vegetable seed crops are our favorites.”

Their ‘Dakota Sport’ tomato is pretty high up there, however. They deemed it another “genetic anomaly” that came out of the heirloom tomato variety, ‘Crimson Sprinter.’

“It just appeared!” Theresa says. “In all of its gorgeous, shiny, candy-apple red, splendor. The flavor and texture! Pure delight just for the picking, and seed saving, of course.”

The gratification that comes from selecting and saving seed from plants that perform well and taste delicious is one reason for the resurgence in seed saving across the country. Theresa believes that seed empowers people to provide for their own food security.

“With the groundswell of local and regional food systems,” Theresa says, “there is a growing recognition that local food security depends on seed security.” She describes their work as filling a crucial need, that seed is “the antidote to hunger and famine.”

Farmers can feed people today and also save seed that will provide countless meals well into the future.

A fundamental difficulty in improving seed, Theresa says, is that too many farmers think of themselves as seed consumers, not stewards. She believes seed stewardship should be inherent to a farmer’s work.

Though seed work isn’t easy, Theresa admits. “Harvesting seed demands repetitive hand labor, which can be hard on muscles and joints,” she says. “We are continually devising ways to streamline our work and make it more ergonomically sustainable. Developing scale-appropriate equipment for seed harvesting and cleaning is also a need.”

Her advice to new seed producers is to start small. Save seed for your own use first. This will allow you to experiment with crops and with varieties, finding those that are adapted and perform well in your region and for which you can produce quality seed.

It all comes back to relationships, Theresa says. “Build a relationship with the crops and varieties you produce and then share that relationship with those with whom you share your seed.”

This post is part of our Farmer Seed Stewardship initiative series. The initiative is a partnership between OSA and Seed Matters, and promotes farmers engagement in seed systems – training farmers in seed production and crop improvement, and advocating for farmers’ ability to save, improve, and plant the seed they need.